Agile Culture

What are Agile organisations and how they look like? Let's explore the key aspects together through this article.

What are Agile organisations?

An organisation becomes Agile when item braces Agile values and principles and applies them to the entire organisation, not just individual teams or projects. Therefore, an Agile organisation is:

- set to succeed in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous environment,

- adapting quickly and easily to internal and external changes,

- continuously learning to better meet user needs and improve itself,

- capable of fast and efficient delivery without compromising on quality,

- sustaining adaptability and flexibility over a long time.

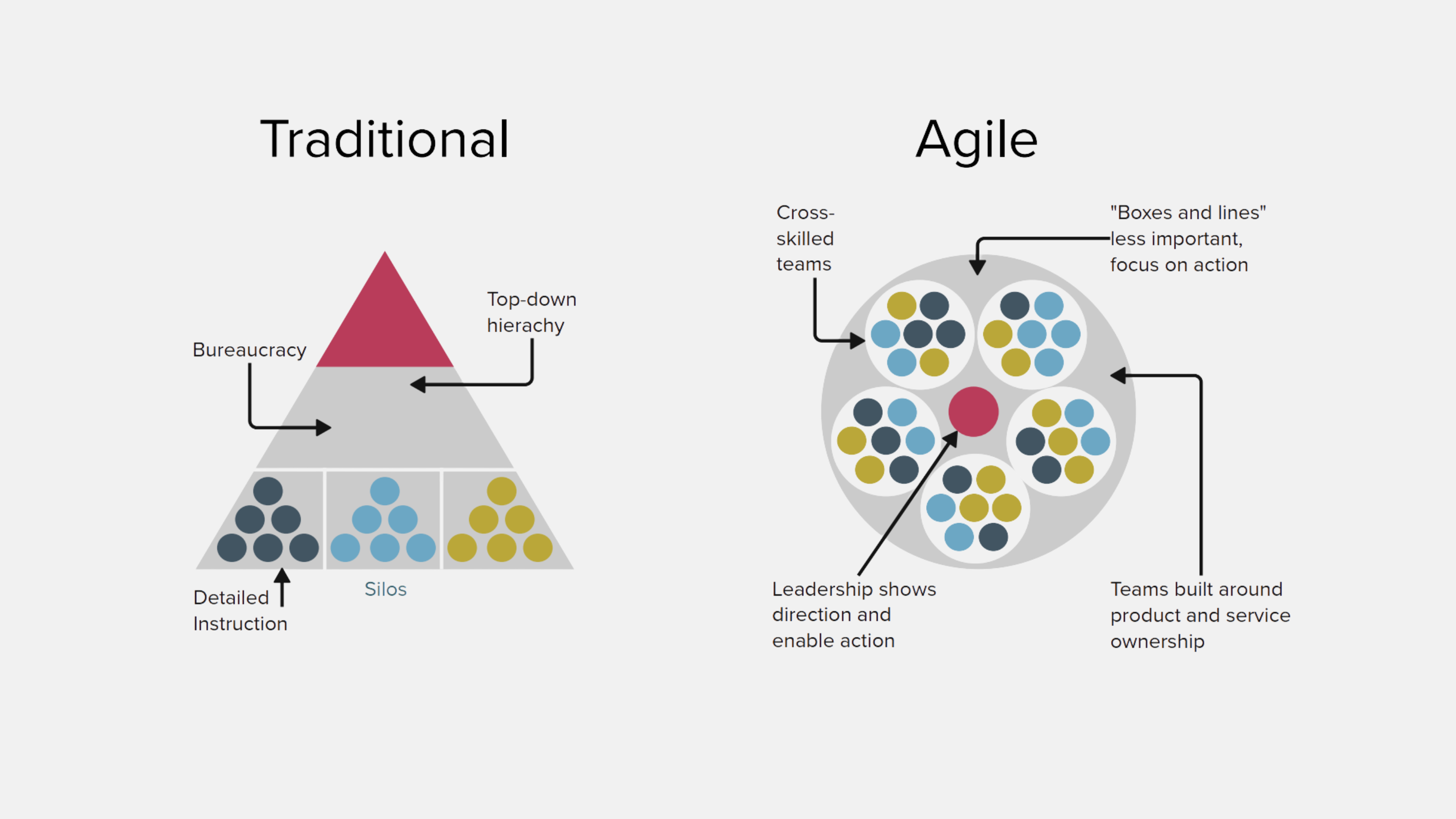

From a helicopter view, we'd see that anAgile organisation is made of autonomous teams built around products or services. While traditionally teams would be made of specialists with a similar skillset, the teams in an Agile organisation tend to consist of people of multiple skills so that they would be able to do whatever is required to produce and deliver value to the users.

The issue with siloed hierarchical structures

To understand why certain types of organisational structures are preferred byAgile organisations, we'll start by exploring the consequences of the traditional approach to structuring the organisation. You might find the description of the traditional organisations as exaggerated, but that is done on purpose - it will help later with explanation of Agile organisation by contrasting them to the interpretation of traditional structures presented here

-

-

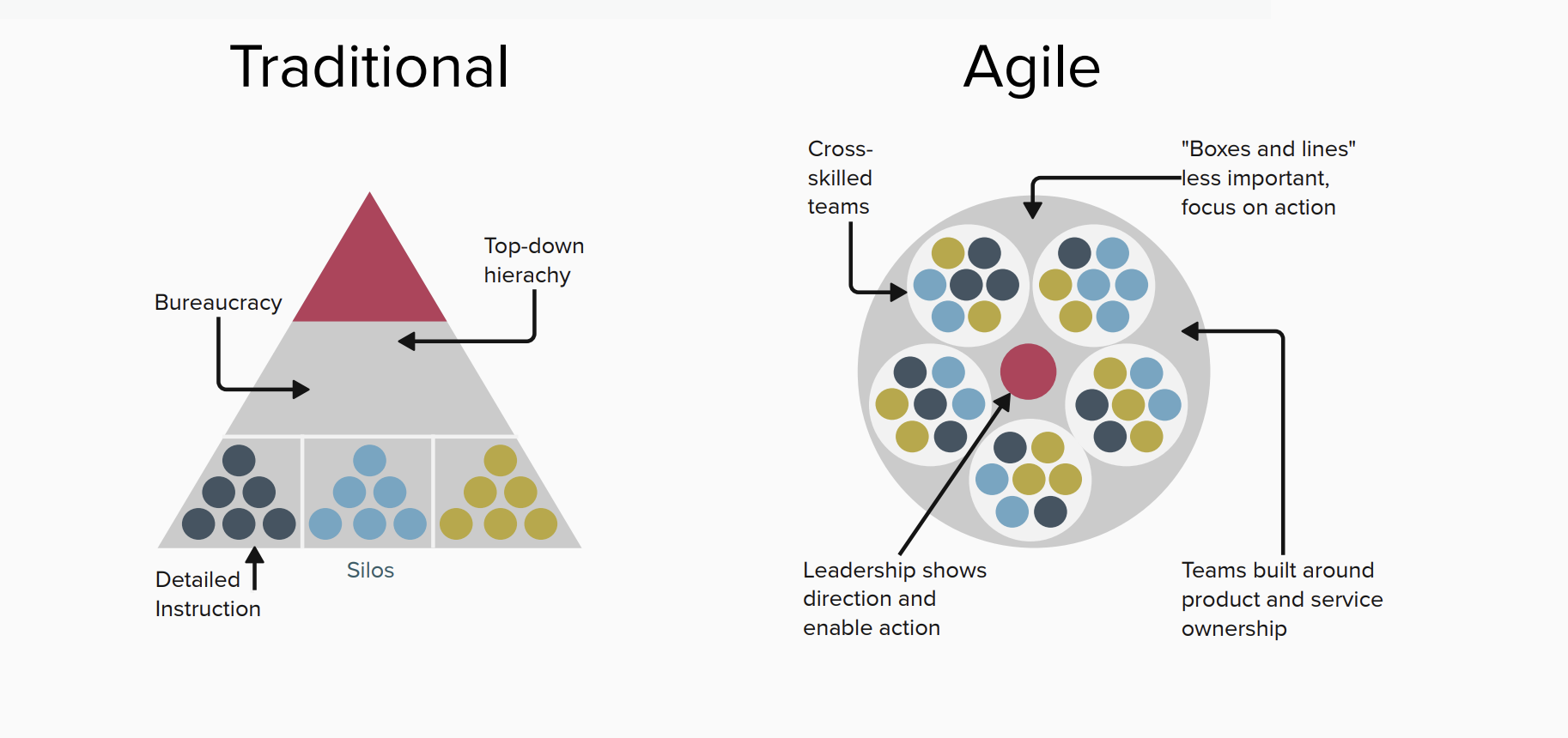

Firstly, we need to recognise that the goal is to find the most effective organisation at producing and delivering value to the users. To achieve that, the organisation needs to perform certain work, which typically is divisible into individual activities (or actions) to be completed by individuals (or small groups of them). Let's consider the following sequence of activities:

Since the sequence contains abstract names of the activities, let's explore examples of real sequences you might be familiar with. In software development, such sequence might be made of requirement gathering, design, development, testing and deployment. In data science, this might be problem framing, data collection and cleaning, exploratory data analysis, modelling, visualisation and reporting, and finally deployment. When discussing organisational structure, you may consider any sequence of activities that is close to your everyday work.

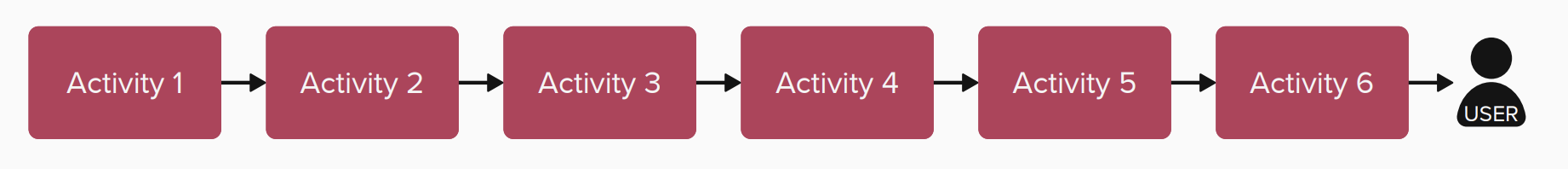

Traditionally, organisations were forming teams of individuals with similar skillset. So we could see team of a business analysts, separate team of architects, separate team or teams of developers etc. This approach yields some benefits, e.g. team members could learn from each other, establishing and maintaining standards for each profession was relatively easy, the line manager for the team is likely to be an experienced and knowledgeable practitioner in the knowledge area relevant to the team. The job of manager of the team includes ensuring each member of the team efficiently executes the allocated tasks, while distributing workload in the respective functional area across the team members.

These teams of specialists are then grouped together based on how similar they are to each other. Departments (or whatever nomenclature is used) will be made of teams working on the same IT system, using the same technology, within the same geographical location, or teams grouped on other criteria that is considered suitable by management to ease management of work and costs across the organisation. The siloes are born so with each added organisational level, more managers and more bureaucratic processes are needed to ensure effective communication and coordination across the organisation.

The paradigm behind this organisational design seems to be a belief that efficient execution of individual activities leads high productivity of the entire organisation. To see what is the main problem with this approach, we need to change our perspective:

- instead of focusing on individual workers, let's look at the flow of work across the entire organisation,

- instead of maximising performance of each worker, let's minimise the time the organisation takes to produce and deliver value to the user.

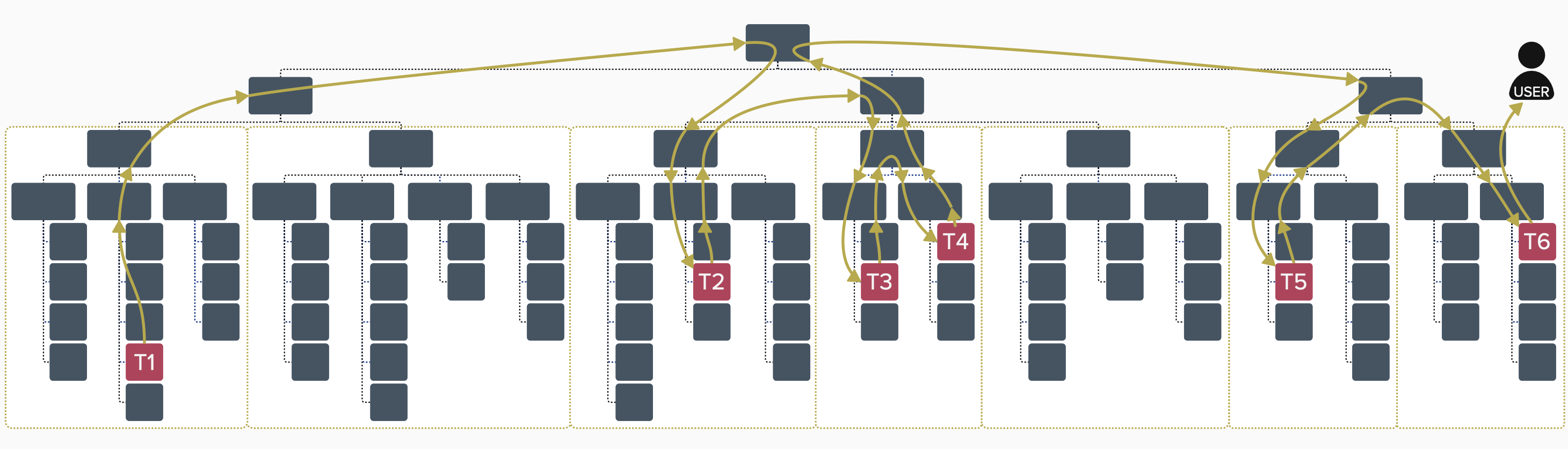

Below is an illustration of how a typical hierarchical, siloed organisation would look like. Since the teams are specialised, Activity 1 can be only done by someone from team T1, Activity 2requires involvement of team T2, etc.

Now think about the realities in working in any large, complex organisation. Do you think that people working on the activities, i.e. those from teams T1 to T6 will work closely together and seamlessly communicate and hand over work to the next person? The tasks are allocated to each of them by their managers, based on the priorities and objectives allocated by the department head. The perception of how urgent and important it is to work on the relevant activity may differ across management in different parts of the organisation. Also, some of the involved teams will be more busy than other. All of this leads to very fragmented flow of work across the organisation and loss of focus on getting the ultimate deliverable to the user as fast as possible. Together with work management system based on communication and control following the vertical lines, the flow of work and information may look like something like this:

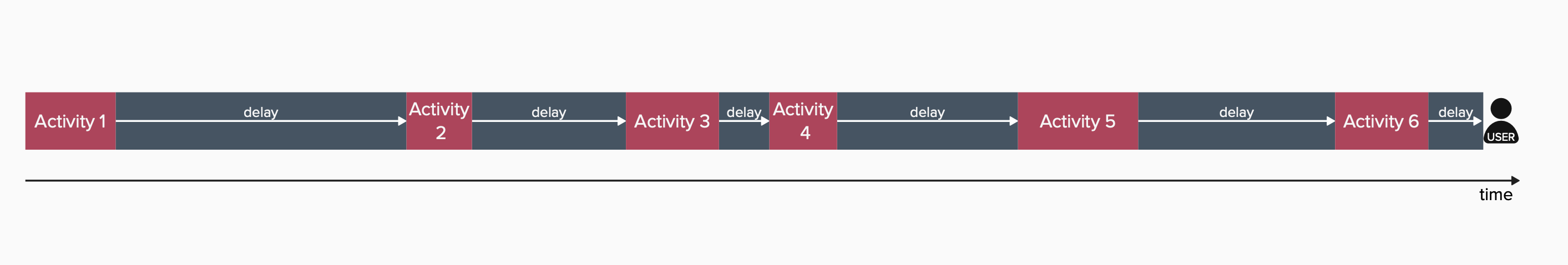

As a result, the sequence of activities required to deliver value to the user is spread widely on the time axis and may look similar to this:

This time axis shows a rather optimistic scenario where the work is not stalled unreasonably and when it does not need to go back to previous team. However, even the happy scenario reveals the flow in thinking be when designing traditional hierarchical organisations: the assumption that maximising performance of individual workers assures optimal performance of the whole organisation. When those organisations to pursue gains in individual performance, they introduce structures that result in delays in the flow across the organisation. Looking at the image above, is this really the right thing to focus on rescuing the duration of Activity 1? Wouldn't it be amore significant improvement in organisational performance if we reduce the delays between the activities?

So far we were talking only about the speed of delivery. However, this fragmented flow of work causes other issue as well. Dividing the workforce based on the skills/competences forces the work to be chopped in a similar fashion. We are ending up with tasks that often have little meaning from end-user's perspective. Since the organisation wants high-performing teams and individuals, the staff will have performance objectives related to own domain of work. Because of focus on completing tasks, instead of focusing actual user needs, the value of the products of the work might not be what the user needs the most. Not because of lack of will among those doing the work, but because they have been so isolated from the actual users - the organisation is not making it easy for most of own employees to understand what value they are supposed to generate for the user.

Overall, while the traditional approach to organisations may work in some situations (e.g. on the production line in manufacturing), they would not be up to the mark when we are dealing with a lot of uncertainty and complexity. In those cases, time to deliver and learn based on feedback is crucial. Therefore, a new approach to the organisation is needed. Next you will learn how most Agile organisations structure themselves to minimise the time to learn.

Agile structures

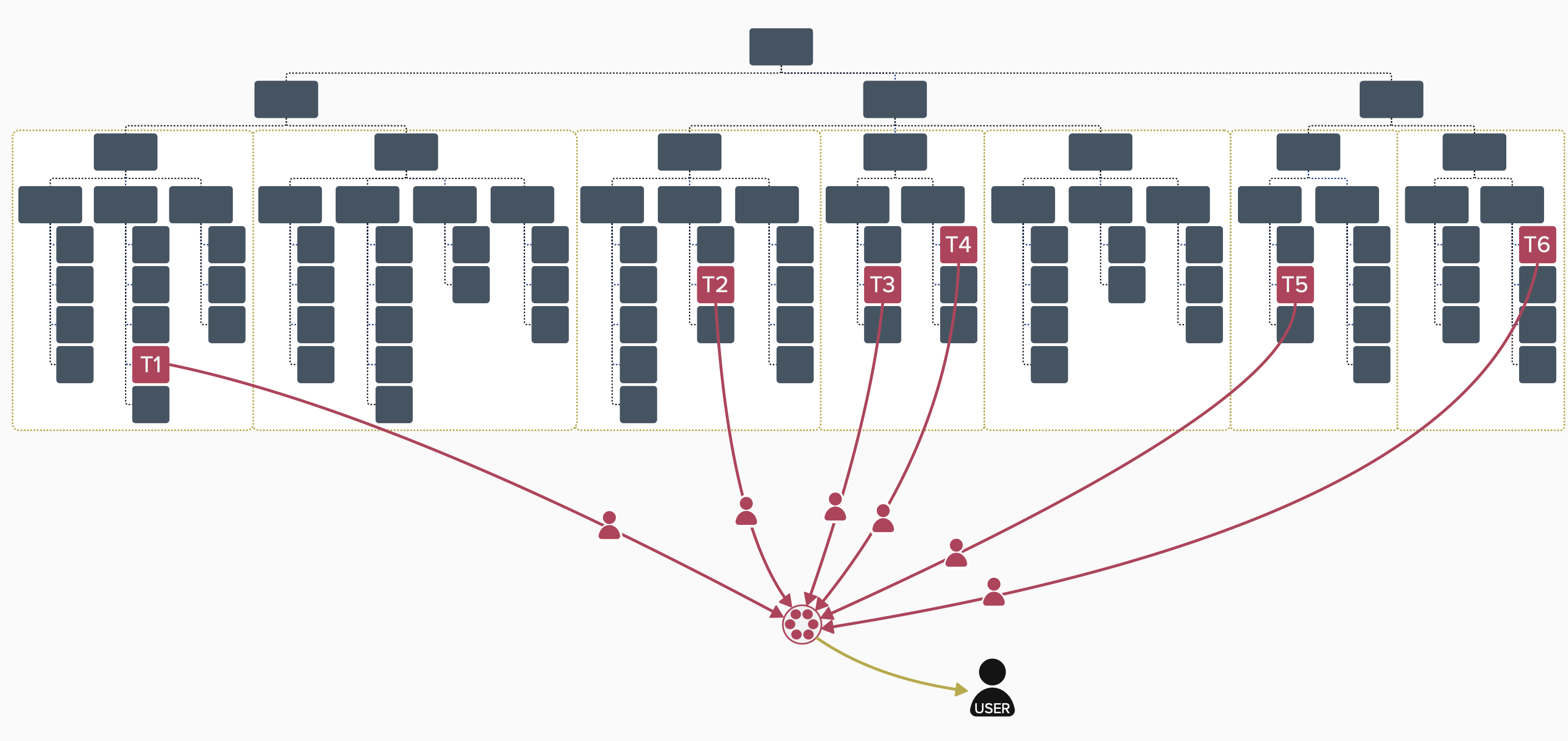

However, since our goal is not to create a single Agile team, but for the entire organisation to become Agile, we repeat the products and services have Agile teams created to develop and deliver them. As a result, we can end up with a plethora of multi-disciplinary teams and to cope with the scale some form of hierarchy might be necessary. The hierarchy in an Agile organisation isn't the same as in the traditional approach - in an Agile organisation teams that have the most need to collaborate will be grouped together, e.g. all of the teams working on a portfolio of products developed for similar group of users, will form a structure that can be seen as a team of teams. This extra 'layer' is not to top-down manage the teams, but to facilitate and enable the teams to interact with each other directly. We create opportunities for collaboration between members of different teams, not introducing intermediaries, rigid control mechanisms or bureaucratic processes that may hamper or slow down the communication.

Additionally, such Agile organisation is evolving dynamically - structure that optimal today, may be obsolete tomorrow. That adaptability of the structure is a direct consequence of Agile principles, since continuously learning what to work on to maximise value to the users, we can also discover that it would be more optimal to move people or teams between products or services. Since there is value in retaining team stability, it typically is preferable move the entire teams. As a result, we have an organisation that behaves more like a living organism that morphs itself to adapt to external conditions, rather than rigid structure that are difficult to change once it's established.

Communities of Practice

We know already that Agile organisations tend to be made of multi-disciplinary teams. Representatives of different professions are now team mates, able to talk each other without the need to navigate through organisational structure. While this results in the benefits which were already discussed, it also has less favourable consequences. These same team members might now be the only representatives of own profession on the team with no obvious opportunities to learn from others or discuss the standards for the profession to be uphold in the organisation. This is whereCommunities of Practice come in - each Community of Practice (CoP) is essentially a group of individuals who come together to share ideas, develop expertise, each other, and solve problems around a specific topic of interest.Any member of the organisation can join one or multiple CoPs, but they shall participate voluntary. While the organisation supports the CoPs, these communities are managed from within.

Self-organising teams

While all Agile teams tend to be multi-disciplinary, not every multi-disciplinary team is automatically an Agile team. Another crucial characteristic of Agile teams is that they are self-managing and self-organising.

There is plenty of very good literature dedicated to self-organising teams. To avoid duplication, I recommend you reading through Mike Cohn's article dedicated to the subject if you wish to familiarise yourself with the topic.

If you are worried that self-organisation means lack of coordination and overall chaos in the teams and wider organisation, you will probably find Henri’k Kniberg’s explanation of aligned autonomy helpful. Watch his video from 3:06 to 4:09 as a minimum, although you will probably find the entire video interesting and inspiring.

Agile Culture

When discussing Agile organisations, we cannot forget about the organisational culture. According to the 17th State of Agile Report, culture clash (general organisational resistance to change) is seen as the most common barrier to Agility (with 47% of survey respondents indicating so).

.png)

Similar conclusions can be drawn from. previous editions of the report. So, the organisational culture may need to change towards Agile culture. But what does Agile culture actually mean? According to Agile Business Consortium,

"Agile culture is about creating an environment that is underpinned by values, behaviours and practices which enable organisations, teams and individuals to be more adaptive, flexible, innovative and resilient when dealing with complexity, uncertainty and change."

To start building Agile culture we need to look into our mindset first. Your mindset is how you think about acting in a given situation, in other words - the thinking that drives your action. It consists of your values, beliefs and principles. Values represent what you consider most important in the given situation, beliefs tell us what you hold to be true in that type of situation, and principles describe the standards that guide your decisions and choices. Reflect on your own mindset, is it truly in line with Agile values and principles that you have learned earlier in this course? What about the others around you?

Do you and the others truly consider delivery of value to users to be the most important? Do you observe active seeking of actionable feedback early on the outputs of your work? Are you and others learning continuously about matters that influence team's success and use that knowledge to course-correct? Do you regularly improve process, teamwork and product? Do you and everyone else in your organisation feel safe to admit mistakes and failures?

Work with others in your organisation and help them until everyone can respond with a resounding 'yes' to all of those questions, and your organisation will gradually get closer to the Agile culture that enables your teams' success.

Summary

So that’s it – this is our brief introduction to Agile Organisations. Now you know that, traditionally, coordination in the wider organisation is done through managers, i.e. vertical lines of communication, relying on bureaucratic processes to pass information upwards so that management at the appropriate level can instruct others on the work they need to do. With Agile, the organisational structures are less rigid, flattened and are to be treated as barriers for lateral collaboration between teams.Leadership is still there and still very important, but their role is to show direction and enable multidisciplinary, self-organising and self-managing teams, not to manage the work to be done by the team members.

We’ve already helped dozens of organisations successfully build Agile culture and navigate transformation.

Get in touch and let’s talk about how we can support yours.